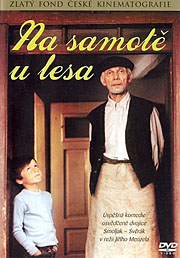

Na samotě u lesa

Na samotě u lesa

Czechoslovakia, 1976, colour, 93 mins

First of all, some much-needed context. Seclusion Near a Forest (also known as A Cottage by the Wood, though the former title is closer to the original) was the second film that Jiří Menzel made after a five-year ban following the reception of Larks on a String (Skřivánci na niti, 1969), which was itself banned until 1990. The first, Who Looks For Gold? (Kdo hledá zlaté dno?, 1974) is generally regarded as a blatant (if understandable) attempt to curry favour with the Communist regime, and is rarely revived, though it did mark the first of four collaborations between Menzel as director and Zdeněk Svěrák as writer (Svěrák had also played minor roles in two of Menzel’s late 1960s films, including Larks on a String).

Seclusion Near a Forest is much closer to the Menzel of old, though it lacks the barbed edge of his adaptations of the work of novelist Bohumil Hrabal. Indeed, to the untrained eye, it resembles a straightforward domestic comedy in which a family of four (parents Oldřich and Věra Lavička and their children Zuzana and Petr) try to fulfil a dream about having their own summer cottage, only to find that the reality doesn’t match up to the fantasy. Much of the running time is taken up with low-level bickering (especially when they end up sharing the cottage with the elderly Mr Komárek and an assortment of fleas) and slapstick interludes (the wheelchair-bound Mr Lorenc involuntarily colliding with a haystack), before everyone comes together in what’s virtually a group hug.

So far so apparently bland – but there’s a fair bit more going on beneath the surface. Seclusion Near a Forest was made at the height of Gustav Husák’s “normalisation” period, which lasted from 1969-89, the year after the Soviet invasion to the Velvet Revolution. While repression in general and cultural repression in particular remained as rife as it had been in the Stalinist 1950s (albeit without the show trials and summary executions), Czechs were encouraged to live outwardly normal lives. They weren’t in any real sense “free”, but they were allowed to purchase consumer goods and holiday cottages in the countryside were by no means idle fantasy – as the film demonstrates. Andrew Roberts’ invaluable essay ‘Normalization and Normal Life in the Films of Ladislav Smoljak and Zdeněk Svěrák’ – see the links below for the full text – cites statistics claiming that by the late 1980s, fully 80% of the Czechoslovak population had at least some access to a summer cottage.

The film depicts the mechanism by which such a cottage might be acquired (including all the bureaucratic stages – Menzel doesn’t dwell on this, but nonetheless makes it clear that such transactions came tightly wrapped in red tape), and the potential drawbacks. By renting a room from the elderly farmer Komárek for 100 crowns a month, the Lavičkas establish themselves as potential purchasers of the entire cottage (for 20,000 crowns), the idea being that Komárek will move to Slovakia to live with his son. Other city-dwellers are doing something similar: the Zvons are pursuing a fantasy of working as millers by purchasing an old mill and paying lip service to the routines, though the flour sacks are actually filled with sand. (One of the film’s comic highlights involves Zvon, played by co-writer Ladislav Smoljak, attempting to lecture about the mill as it is operating, but his voice is inaudible over the clanking, grinding machinery). Meanwhile, the Kokešes have bought a cottage at a discount, achieved by allowing its elderly inhabitants to remain living there until they die – a running gag shows Mr Kokeš devising various stratagems to persuade them to leave early.

By contrast, the Lavičkas get on extremely well with the seventysomething Komárek (Josef Kemr): the children regard him as a substitute grandfather, while Lavička (Zdeněk Svěrák) is always happy to chat to him, and indeed everyone else in the village, with whom he goes out of his way to try to integrate. Věra Lavičková (Daniela Kolářová) takes on the Cassandra role: when she realises that Komárek has no plans to leave and is in robust health, she points out that buying the cottage will achieve nothing aside from a substantial dent in their funds. She’s also much less enamoured of the downside of country living, with its rotten planks, collapsing beds, defecating chickens, goats eating her freshly-baked bread and a plague of dog fleas defying the widely-expressed local adage that they don’t bite people.

Věra’s complaints give the film its dramatic tension, especially in the second half, but Menzel and his writers aren’t interested in family-rupturing rows. But, as Roberts points out, the film’s gentleness can be read in two ways: Menzel, Svěrák and Smoljak go out of their way to set up scenes in which people are given opportunities exploit others for their own gain – and then refuse to let their characters take the bait, as demonstrated by the brief scene in which the representative of the local farming collective is quite happy to sign and stamp Lavička’s form in the middle of the farmyard with no formalities. As with the later (also Svěrák-scripted) My Sweet Little Village (Vesničko má středisková, 1985), the film’s criticisms of the Husák regime are so subtle as to be barely discernible, but it’s likely that domestic audiences were more than capable of reading between the lines: true communal happiness comes from looking out for each other, and ignoring the authorities’ strictures as much as is feasible.

It’s primarily a writers’ and performers’ film, though Menzel’s own distinctive fingerprints can be discerned via the deceptively casual staging of such set-pieces as the opening traffic jam, Zvon’s milling lecture, the alfresco lunch (whose oldest guest is convinced that he’s met the new arrivals before) and quasi-slapstick moments such as the collapsing bed. Also characteristic of Menzel are a handful of seemingly throwaway cutaways, in one oddly memorable case to a close-up of a framed photograph of an elderly couple mounted on Komárek’s bedroom wall – as if to suggest not merely a lengthy ancestral thread but also that life goes on regardless of any day-to-day complications. It’s not quite a feelgood comedy, but it’s certainly closest to that than much of Menzel’s other work.

- Director: Jiří Menzel

- Script: Zdeněk Svěrák, Ladislav Smoljak

- Camera: Jaromír Šofr

- Production Design: Zbyněk Hloch

- Editing: Jiřina Lukešová

- Sound: Adam Kajzar

- Music: Jiří Šust

- Production Manager: Jan Šuster

- Production Company: Barrandov Film Studios

- Cast: Josef Kemr (Komárek); Zdeněk Svěrák (Oldřich Lavička); Daniela Kolářová (Věra Lavičková); Marta Hradílková (Zuzana); Martin Hradílek (Petr); Ladislav Smoljak (Zvon); Naďa Urbánková (Zvonová); Jan Tříska (Dr, Houdek); Zdeněk Blažek (Hruška); Alois Liškutín (Kos); František Řehák (Lorenc); Václav Trégl (Vondruška); Vlasta Jelínková (Vondrušková); Oldřich Vlach (Kokeš); František Kovářík (Komárek senior); Míla Myslíková (Božena); Evžen Jegorov (gamekeeper); Milan Štibich (Co-operative chairman); Petr Brukner (salesman)

DVD Distribution: Centrum českého videa (Czech Republic), PAL, no region code

Picture: The source print is in adequate condition for a thirtysomething film – the colours are somewhat pasty, there are quite a few white dust spots, and occasional glimpses of more serious damage, but nothing that impedes viewing. The transfer appears to have been sourced from an analogue tape (there’s a telltale texturing to the image), its shortcomings becoming particularly clear during scenes in low light, where the lack of shadow detail becomes a problem. But none of it seriously affects viewing pleasure, and it’s a distinct cut above the same label’s My Sweet Little Village. The aspect ratio is 4:3, and there are no compositional or historical reasons why it should be anything else.

Sound: Two soundtracks are on offer: a Dolby Digital 5.1 remix and a Dolby Digital 2.0 track – probably the original mono. Both sounded virtually identical, so I stuck with 2.0 on the grounds that it was probably closest to the version original.

Subtitles: The English subtitles have a few typos, but the translation is always perfectly clear.

Extras: Most of the extras are off limits to non-Czech speakers, but consist of Czech filmographies of Jiří Menzel and his cast, unsubtitled interviews with Menzel (4:36), Zdeněk Svěrák (4:37) and Ladislav Smoljak (5:42), six very short scenes from the film (also unsubtitled) and a stills gallery that plays for 1:15 and is accompanied by the film’s score. There’s also a selection of promotional material from the DVD’s sponsors, and information about other discs in the series (again, all in Czech).

Links

- YouTube has an extract from the film, albeit in unsubtitled Czech.

- České filmové nebe (in Czech)

- Česko-Slovenská filmová databáze (in Czech)

- Internet Movie Database

- Andrew Roberts’ essay ‘Normalization and Normal Life in the Films of Ladislav Smoljak and Zdeněk Svěrák‘ (PDF).

The English subtitles have a few typos