Za króla Krakusa.

Za króla Krakusa.

Poland, 1947, black and white, 14 mins.

One of the peculiarities of Polish film hisory is the almost perfect separation between the pre-1939 and post-1945 eras, for reasons that the dates themselves spell out all too clearly. Many Polish filmmakers didn’t survive World War II, while others chose not to return to Poland afterwards, and in consequence there was little continuity. Indeed, Zenon Wasilewski (1903-66) seems to be just about the only significant name who was active in authentically Polish animation both sides of the war. Originally a cartoonist for the satirical weekly Cyrulik Warszawski, he expanded his range to encompass collage, photographic experiments and eventually animation. He discovered the latter medium in 1935 when he was hired to create drawings for animation pioneer Włodzimiers Kowanko. In 1938, he became a professional animatior, creating short advertisements using plasticine figures.

In 1939, in his own flat, he began to work virtually single-handed on what would eventually become In the Time of King Krakus (the most literal translation of Za króla Krakusa, though it’s also been shown under the alternative titles The Dragon of Cracow and The Wawel Dragon). He completed the animation, and intended to create an accompanying soundtrack, but his plans were interrupted by war, which the film did not survive. Wasilewski spent the war in the Soviet Union, working mainly as an anti-Nazi propagandist. Afterwards, he returned to Warsaw and began to remake his film. He also teamed up with designer Ryszard Potocki to found Studio Małych Form Filmowych in Łódź, the direct ancestor of the famous Se-Ma-For animation studio. There, he made propaganda shorts and completed In the Time of King Krakus, which became renowned as the first important Polish puppet film, and also the first to receive serious international attention.

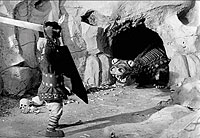

This context is important, because the film itself, while frequently delightful, is no groundbreaker either artistically or technically. To a British viewer, it has much in common with the work of Gordon Murray (Camberwick Green) or Oliver Postgate and Peter Firmin (The Clangers) in its simple puppet designs and occasionally jerky stop-motion animation. Although the citizens of Krakow are terrified of it, the swivel-eyed dragon has more in common with Postgate and Firmin’s soup-dispensing variety than the fire-breathing monster of legend, despite the human and animal skulls dotted around the entrance to his lair – picked clean by a group of predatory crows that flies off whenever things threaten to get rough.

However, the animation of the human characters often shows real skill, especially given the lack of role models that Wasilewski could draw on. The heads are fully articulated, with moving, blinking eyes, the citizens of Kraków alternate alarm and befuddlement when contemplating the dragon’s ravages, while Krakus’ crown slips down over his eyes during his excitement at watching the knight Waligóra trying his luck. Best of all is the animation of the unnamed second knight’s horse as it flies into a bucking, whinnying panic before climbing a tree after his master (whose evil designs on Krakus’ kingdom are indicated by his German accent and a motif that looks very much like a medieval proto-swastika).

This set-piece, with the knight and horse up the tree and the dragon gnawing it down at the base, is comfortably the film’s comic/dramatic high point, though there’s also much to enjoy in the climactic scenes in which the lowly cobbler’s apprentice Skuba attempts to defeat the dragon using ingenuity rather than brute force, stuffing a black ram’s carcass with unspecified poison – sulphur, according to legend, which gave the dragon an incredible thirst that led its stomach to explode after ingesting half the Vistula river.

King Krakus himself (c. 12th century) was a real-life historical figure, after whom Kraków is named – he’s also credited with building Wawel Castle, allegedly on top of the cave inhabited by the dragon. The latter is such an indelible part of local folklore that there’s even a statue to it in the cathedral, plus a fire-breathing version in front of its lair, while the Kraków Film Festival awards Gold, Silver and Bronze Dragons. Perhaps in an attempt to make the film more child-friendly, Wasilewski plays down one element of the legend, which is the dragon’s specific predilection for young girls to the point where Krakus’ daughter Wanda is the only one left. She’s present in the film (under the name Ludmila), but only as a doe-eyed bounty for the victor.

- Director: Zenon Wasilewski

- Script: Zenon Wasilewski

- Photography: Eugeniusz Haneman

- Puppets: Zenon Wasilewski

- Set Decoration: Zenon Wasilewski

- Assistant Decorator: Edward Sturlis

- Costumes: Irena Wasilewska

- Music: Stanisław Wisłocki

- Sound: Józef Koprowcz

- Production Managers: Mieczysław Weinberger, Jan Łopuszniak

- Characters: King Krakus; Queen Ludmiła; Skuba the Cobbler; Waligóra the Knight; The German; Knights; People of Krakow

DVD Distribution: In the Time of King Krakus is included in the Anthology of Polish Children’s Animation (Antologia polskiej animacji dla dzieci), distributed by Polish Audiovisual Publishers (Polskie Wydawnictwo Audiowizualne/PWA) in Region 0 PAL.

Picture: The print begins in alarmingly ropey fashion, with scratches, exposure fluctuations and other evidence of long-term neglect, but things improve noticeably after the titles end – though there’s still visible damage, the occasional jump-cut and a number of blatantly overexposed images (though these are probably technical errors on Wasilewski’s part). Given the quality of the rest of the DVD set, it’s highly likely that these were the best materials available.

Sound: As one would expect, the sound is monophonic, with a fair amount of crackle and hiss betraying its age and low-budget roots. But it’s always perfectly comprehensible.

Subtitles: Unusually for a Polish animated film, In the Time of King Krakus has an almost continuous voiceover narration, but the optional English subtitles are fine bar the occasional typo.

Links

- BFI Film and TV Database

- Filmpolski.pl database

- Wikipedia articles on King Krakus and the Wawel Dragon