Sztandar Młodych.

Sztandar Młodych.

Poland, 1957, tinted monochrome, 3 mins.

A three-minute advertisement for the Polish Communist daily youth newspaper Sztandar Młodych (‘Banner of Youth’), this is a more or less exact equivalent of the films that Len Lye made for the GPO Film Unit in Britain twenty years earlier. Lye’s A Colour Box (1935) was an abstract film made by painting directly onto celluloid, while Trade Tattoo (1937) made creative use of partially solarised live-action footage, onto which he’d stencil and paint his own designs – though each film had a specific advertising purpose, this very much played second fiddle to their exuberant invention. Lye’s films, and those of Norman McLaren, his most obvious successor, were also renowned for their jazzy rhythms (McLaren worked with the great Oscar Peterson on Begone Dull Care, 1949), which would remain all too apparent in the celluloid even if played silent.

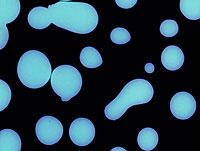

Walerian Borowczyk and Jan Lenica’s film is very much in the Lye/McLaren mould, and was apparently one of the earliest near-abstract films to be made in Poland. To a brassy up-tempo jazz number (of a kind that would have been off limits to Polish filmmakers only a couple of years earlier), the filmmakers assemble a rapid-fire montage consisting of repeated still shots of an eye, hand-drawn horizontal and vertical lines, dots and other shapes, and high-speed live-action footage of rally races (complete with crashes), ski jumpers, competitive cyclists and boxers. The music continues in an identical vein even when the images become more newsy: a military flypast, visiting dignitaries, marching soldiers and a burning building – occasionally, sound effects (marching footsteps, crackling flames) are laid over the image.

The eye keeps staring straight ahead (though the increasingly rapid intercutting makes it appears to blink throughout) as the film moves into its third section, celebrating the space race (which had then only just begun), before coming back down to earth for a final montage intercutting jazz performers (their naturally black or white skin deliberately confused by processing the film as alternating positive and negative images) and a somewhat fetishised collection of still images of shoes and fashion models that offers an early hint of Borowczyk’s future erotic preoccupations. By this stage the abstract elements have worked themselves up into a tangled frenzy, as if overcome with the excitement of… well, presumably everything to be found within the pages of a typical issue of Sztandar Młodych. “CZYTAJ SZTANDAR MŁODYCH!” (“Read ‘The Banner of Youth’!”), we are exhorted at the end, but by this stage how can we resist?

Sztandar Młodych itself had a very long life. First published in 1950, it almost managed a half-century before ceasing publication in 1997. Amongst its more distinguished contributors were the journalist Ryszard Kapusciński, who started his career with the paper in 1955, and Aleksander Kwaśniewski, who edited it in 1984-85, a decade before succeeding Lech Wałęsa as Poland’s second post-Communist President. For much of its life, the paper was effectively the mouthpiece of the communist Polish Youth Union (Związek Młodzieży Polskiej, or ZMP).

- Directors: Walerian Borowczyk, Jan Lenica

- Photography: Edward Bryła

- Production Company: Wytwórnia Filmów Dokumentalnych (WFD)

DVD Distribution: The Banner of Youth is included in the Anthology of Polish Experimental Animation (Antologia polskiej animacji eksperymentalnej), distributed by Polish Audiovisual Publishers (Polskie Wydawnictwo Audiowizualne/PWA) in Region 0 PAL.

Picture: Given that the film consists of a mixture of grainy found footage and hand-painted celluloid, it’s hard to reach a definitive assessment of print quality, but it appears very clean and there are no issues with the transfer. The 4:3 aspect ratio appears to be correct (and one wouldn’t expect anything else for this era in Polish cinema).

Sound: There’s a pronounced crackle at the start but it’s safe to assume that it’s inherent in the original materials. Otherwise, it’s typical 1950s mono, and perfectly adequate for the task in hand.

Subtitles: There’s just one subtitle, and even that’s arguably superfluous (it’s translated above, for starters) – but it’s available if desired.