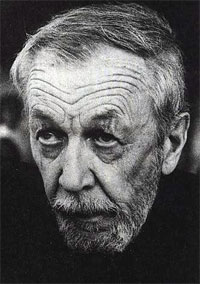

The recent retrospectives and DVD boxes of films by the long-neglected Japanese master Mikio Naruse serve to emphasise the wealth of important cinema that still remains to be discovered outside the established canons. František Vláčil (1924-1999) may be Naruse’s closest equivalent in Czech cinema, not because their aesthetic and thematic preoccupations have much in common, but because he’s an unquestionably major talent who has been almost entirely ignored outside his native country, except in the most specialist critical circles.

The recent retrospectives and DVD boxes of films by the long-neglected Japanese master Mikio Naruse serve to emphasise the wealth of important cinema that still remains to be discovered outside the established canons. František Vláčil (1924-1999) may be Naruse’s closest equivalent in Czech cinema, not because their aesthetic and thematic preoccupations have much in common, but because he’s an unquestionably major talent who has been almost entirely ignored outside his native country, except in the most specialist critical circles.

And yet the first few shots of Marketa Lazarová (1967) alone make it clear that here is an artist with a quite exceptional cinematic sensibility. Taking an overwhelmingly visual approach, Vláčil thrusts the viewer straight into an alarmingly convincing medieval environment without so much as a by-your-leave, from the opening dolly shot of a pack of wolves roaming the snowy wastes, through the early scenes in which the camera appears to crouch amongst the foliage as if trying to hide from both human and natural predators. It’s a disorientating experience, but also an exhilarating one, its sheer sweep and ambition and its intricate visual poetry amply compensating for any first-time bewilderment, and its elemental physicality made it unprecedented in both Czech and world cinema.

Born on 19 February 1924, Vláčil originally studied art history and aesthetics before spending the 1950s dabbling in various media (including puppet animation) before turning to live-action filmmaking. Initially seconded to the Czech Army Film Unit, for whom he made documentaries (and gained useful experience in working under difficult conditions), he first made his reputation with the Venice Film Festival prizewinner Glass Skies (Skleněná oblaka, 1957), a 20-minute short that tells a virtually wordless story of a young boy and an old man bonding through their shared love of flying. He then made Pursuit (Pronásledování), part of the portmanteau film No Admittance (Vstup zakázán, 1959).

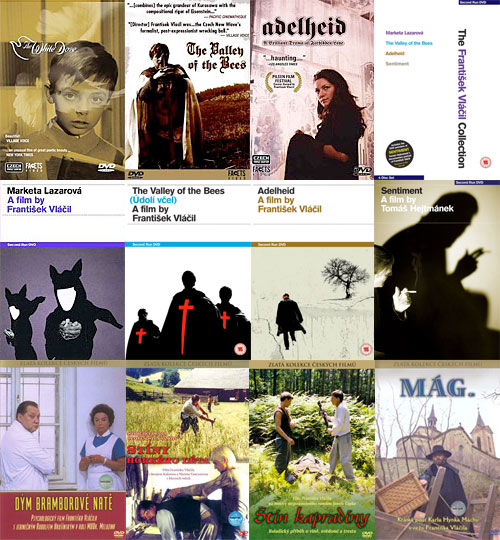

Vláčil ‘s feature debut came in 1960 with The White Dove (Holubice), which represented Czechoslovakia at that year’s Venice Film Festival and is considered one of the first films to be made in the spirit of what eventually became the Czechoslovak New Wave. A low-key fantasy, not dissimilar to Albert Lamorisse’s classic The Red Balloon (Le Ballon rouge, 1956), it crosscuts the experiences of a young girl in an unnamed Baltic country awaiting the arrival of the homing pigeon of the title, a wheelchair-bound boy in Prague who inadvertently intercepts it, and his neighbour, an artist who tries to teach him the importance of respecting living creatures through his preferred medium. As with many of Vláčil’s films, dialogue is kept to a barely functional minimum, as he prefers to explore his themes through a strikingly inventive use of landscape and architectural space. It also marked his first collaboration with the prodigiously inventive composer Zdeněk Liška, who would score all his films for the next seventeen years.

Vláčil ‘s feature debut came in 1960 with The White Dove (Holubice), which represented Czechoslovakia at that year’s Venice Film Festival and is considered one of the first films to be made in the spirit of what eventually became the Czechoslovak New Wave. A low-key fantasy, not dissimilar to Albert Lamorisse’s classic The Red Balloon (Le Ballon rouge, 1956), it crosscuts the experiences of a young girl in an unnamed Baltic country awaiting the arrival of the homing pigeon of the title, a wheelchair-bound boy in Prague who inadvertently intercepts it, and his neighbour, an artist who tries to teach him the importance of respecting living creatures through his preferred medium. As with many of Vláčil’s films, dialogue is kept to a barely functional minimum, as he prefers to explore his themes through a strikingly inventive use of landscape and architectural space. It also marked his first collaboration with the prodigiously inventive composer Zdeněk Liška, who would score all his films for the next seventeen years.

Vláčil then made the first of several trips into the distant past, turning to 16th-century Bohemia for The Devil’s Trap (Ďáblova past, 1961), a thinly veiled political allegory in which the Inquisition investigates a minor on suspicion of being in cahoots with the Devil, because of his seemingly supernatural knowledge of his local environment – which is actually a product of ancient family secrets passed through the generations.

Then came Marketa Lazarová, Vláčil’s third feature and his acknowledged masterpiece. It was shot on a huge budget over a two-year period, during which Vláčil immersed himself in the medieval era both in terms of study and physical reconstruction. He told the critic Antonín Liehm that “whenever I watch a historical film, I always felt as if I were seeing contemporary people all dressed up in historical costumes. I wanted to understand them, see through the eyes of their lives, their feelings, their desires – in short, I wanted to drop back seven centuries.” Largely ignored by the West, which tended to associate Czech cinema with low-key humanist dramas of Miloš Forman and Jiří Menzel, it was voted the best Czech film of all time by a poll conducted in 1998.

Then came Marketa Lazarová, Vláčil’s third feature and his acknowledged masterpiece. It was shot on a huge budget over a two-year period, during which Vláčil immersed himself in the medieval era both in terms of study and physical reconstruction. He told the critic Antonín Liehm that “whenever I watch a historical film, I always felt as if I were seeing contemporary people all dressed up in historical costumes. I wanted to understand them, see through the eyes of their lives, their feelings, their desires – in short, I wanted to drop back seven centuries.” Largely ignored by the West, which tended to associate Czech cinema with low-key humanist dramas of Miloš Forman and Jiří Menzel, it was voted the best Czech film of all time by a poll conducted in 1998.

Vláčil stayed in the medieval era for Valley of the Bees (Údolí včel, 1967), though stylistically it was quite different. Whereas Marketa was wild and untamed, Valley is formal and rigorous, appropriate for its theme of a young man (Petr Čepek) forcibly raised as a member of the Teutonic Order of St Mary of Jerusalem and required to dedicate every fibre of his being to their cause, renouncing family and earthly pleasures alike. He eventually escapes and returns to his old home, where he falls in love with his stepmother – technically incest, despite their lack of blood ties. There’s also a thinly veiled gay subtext of a kind that was highly unusual for 1960s cinema generally, never mind from a Communist country.

The last of Vláčil’s films that’s reasonably accessible to English speakers is the 1969 Adelheid. Shot in colour for the first time since his 1950s shorts, it was set at the end of World War II, at a time when Germans were declared second-class citizens and expelled from Czechoslovakia, regardless of whether they’d lived there all their lives. Petr Čepek again stars as a Czech airman who returns to his native country to reclaim an estate formerly held by a Nazi collaborator. He discovers that the German’s daughter Adelheid is working as a general dogsbody, and the two begin a wary relationship, hampered by their lack of knowledge of each other’s languages and a secret that she withholds from him until the film is nearly over.

The last of Vláčil’s films that’s reasonably accessible to English speakers is the 1969 Adelheid. Shot in colour for the first time since his 1950s shorts, it was set at the end of World War II, at a time when Germans were declared second-class citizens and expelled from Czechoslovakia, regardless of whether they’d lived there all their lives. Petr Čepek again stars as a Czech airman who returns to his native country to reclaim an estate formerly held by a Nazi collaborator. He discovers that the German’s daughter Adelheid is working as a general dogsbody, and the two begin a wary relationship, hampered by their lack of knowledge of each other’s languages and a secret that she withholds from him until the film is nearly over.

After Adelheid, Vláčil found his career hampered by state opposition. After a few years’ making short films for children (one of which, the 50-minute Sirius, 1974, won the Grand Prix at the Tehran Children’s Film Festival) and a documentary on Prague’s Art Noveau history, he returned to fiction features with Smoke on the Potato Fields (Dým bramborové natě, 1976), a simple, lyrical story about a lonely doctor who copes with his wife’s permanent emigration by relocating to a small provincial town that reminds him of his childhood. This was followed in quick succession by Shadows of a Hot Summer (Stíny horkého léta, 1977), a kind of Moravian Straw Dogs in which a man is forced to draw on his darkest impulses to protect his family from a gang of bandits. It shared the Grand Prix at the Karlovy Vary Film Festival.

Vláčil’s final films have barely been seen outside his native country. Concert at the End of Summer (Koncert na konci léta, 1979) was a biography of the composer Antonín Dvořák, made to mark the 75th anniversary of his death. Serpent’s Poison (Hadí jed, 1981) examined the relationship of a young woman and her increasingly alcoholic father. A Little Shepherd Boy from the Valley (Pasáček z doliny, 1983) portrayed a young boy being forced to live with strangers at the end of the war, while Shadow of a Fern (Stín kapradiny, 1985) was a hallucinatory, uncharacteristically talky study of two men on the run after killing both a deer and a gamekeeper. Finally, The Magus (Mág, 1987) portrayed the last years of the Czech poet Karel Hynek Mácha. Vláčil lived long enough to see Marketa Lazarová acclaimed as the best Czech film of all time, and to receive a lifetime achievement award at the 1998 Karlovy Vary Film Festival, just months before his death on 28 January 1999.

Vláčil’s final films have barely been seen outside his native country. Concert at the End of Summer (Koncert na konci léta, 1979) was a biography of the composer Antonín Dvořák, made to mark the 75th anniversary of his death. Serpent’s Poison (Hadí jed, 1981) examined the relationship of a young woman and her increasingly alcoholic father. A Little Shepherd Boy from the Valley (Pasáček z doliny, 1983) portrayed a young boy being forced to live with strangers at the end of the war, while Shadow of a Fern (Stín kapradiny, 1985) was a hallucinatory, uncharacteristically talky study of two men on the run after killing both a deer and a gamekeeper. Finally, The Magus (Mág, 1987) portrayed the last years of the Czech poet Karel Hynek Mácha. Vláčil lived long enough to see Marketa Lazarová acclaimed as the best Czech film of all time, and to receive a lifetime achievement award at the 1998 Karlovy Vary Film Festival, just months before his death on 28 January 1999.

At the time of writing, eight of Vláčil’s films are available on DVD across three labels, together with Tomáš Hejtmánek’s Vláčil-inspired quasi-documentary Sentiment. The most consistently high-quality label is Second Run (UK Region 0 PAL), all of whose releases (Marketa Lazarová, Valley of the Bees, Adelheid, Sentiment) offer excellent transfers, subtitles and booklets with substantial essays by Peter Hames. Facets (US Region 0 NTSC) beat them to the marketplace by a few years, but all three of their discs (The White Dove, Valley of the Bees, Adelheid) are flawed by poor transfers and out-of-sync subtitles. The Second Run options are far preferable, though The White Dove remains exclusive to Facets as of December 2010. The other four films are Smoke on the Potato Fields, Shadows of a Hot Summer, The Shadow of the Fern and Mág, all of which are out on the Czech Bonton label in unsubtitled Czech. However, .srt subtitle files for all four releases are also available (email me if you have difficulty finding them).

Further reading

Peter Hames has written extensively about František Vláčil in the books The Czechoslovak New Wave and The Cinema of Central Europe (both Wallflower Press), the booklet accompanying Second Run’s DVDs of Marketa Lazarová, Valley of the Bees and Adelheid and one-off articles such as ‘In the Shadow of the Werewolf‘ (Kinoeye, 16 October 2000). Facets’ Vláčil DVD releases are accompanied by 12-page booklets with an informative essay by Susan Doll. I wrote a general overview of Vláčil’s work for Sight & Sound (available here). Czech speakers have far more material to draw on, starting with this extensive tribute website hosted by Nostalghia.cz – with plenty of illustrations on offer for those who can’t read the text.

Fascinating article and thoroughly researched, as always. I know a bit about Czech cinema, but must admit that Vlacil so far had escaped my attention. I will surely order “Marketa Lazarova” from Second Run.

By the way, I totally agree with Vlacil’s remark that “whenever I watch a historical film, I always felt as if I were seeing contemporary people all dressed up in historical costumes”. Yes, indeed. The only film where I had the feeling I was really watching people from a distant epoch was Kubrick’s “Barry Lyndon”. I’m most curious to see how Vlacil himself managed that problem in “Marketa Lazarova”.

Hey, I was just thinking about Vlacil! There is a fantastic biopic, with Jiri Kodet as Vlacil, based on interviews that the director, Tomas Hejtmanek, carried out with Vlacil in an old-age home just before he died. Sentiment (2003) was shown at Finale in Plzen in 2004 and seems to have disappeared with no commercial release. This is a real shame as Kodet’s performance is masterful and the film revisits the sites of Vlacil’s films and the crew are shown standing still and recording the atmosphere. There are no clips from his films, only excerpts from the soundtracks.