Édes Emma, drága Böbe

Édes Emma, drága Böbe

Hungary, 1992, colour, 81 mins.

István Szabó’s return to his native Hungary after over a decade of international acclaim produced a film that’s a stark contrast not only to the glossy, star-studded production values of Mephisto (1981), Colonel Redl (1985), Hanussen (1988) and Meeting Venus (1991), but also to the euphoria that greeted the collapse of communism in central and eastern Europe in 1989. The widespread impression given by the Western media was that some kind of switch had been thrown, instantly turning totalitarian states with centrally-planned economies into thriving, vibrant and free democracies. This was easy enough to swallow if you didn’t actually set foot in those countries in the early 1990s, but residents who had experienced the sharp end of an unprecedentedly abrupt transition to capitalism knew rather better. The downsides of the post-communist experience would go on to become an increasingly familiar theme, but Szabó was one of the first major directors to tackle it in (barely) fictionalised form less than three years since the Berlin Wall came down.

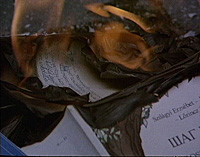

The film’s full title, Édes Emma, drága Böbe, vázlatok, aktok, translates as “Sweet Emma, Dear Böbe, Sketches, Nudes”, though any hint at eroticism is banished by the opening shot of a naked woman rolling helplessly down a steep, grey, dusty escarpment. Occasionally she’ll grab at a root or similar outcrop, but nothing can halt her fall. It’s a recurring dream, and if its symbolism is none too subtle, that’s appropriate for a film that’s primarily intended as a wake-up call. The dreamer is Emma (Dutch actress Johanna ter Steege), a teacher who’s been forced by circumstance to switch from Russian to English after the former becomes not merely redundant but politically suspect. Early on in the film, in one of many clashes with her pupils and colleagues that pepper the film, she catches the kids burning a pile of Russian textbooks and exercise books while mockingly singing the Volga Boat Song.

Emma and her friend Böbe live a life of near-destitution in a squalid block of flats housing 300 teachers, two to a tiny room and a communal shower block (whose users screw their own shower heads into the pipe, in one of many small but telling details). Privacy is nonexistent without prior arrangements, and Böbe is long past caring: she lives off restaurant meals paid for by foreign men, and is happy to repay them in her bed, regardless of whether Emma is trying to sleep only a few feet away. Emma herself is far less promiscuous, since she still believes she stands a chance with Stefanics, the headmaster of her school, despite all his indications to the contrary. Aside from anything else, he’s not only married but desperate to avoid any whiff of public scandal: as someone who rose to his present position under the Communists, he knows that even the mildest infraction could destroy his career.

Szabó sketches in the ghastliness of life in early 1990s Budapest in a few brief but vivid vignettes: the foul-mouthed conversations of youths on Emma’s tram, the attempted rape followed by a police interview that seems to be just as lip-smackingly intrusive, an argument over grades in which Emma vehemently denounces the “all must have prizes” approach against an official line of utter cynicism (“we’ll never see them again, so why not give them good grades?”), Emma’s mother trying to lure her daughter home through bribery rather than affection (”they’re giving back the nationalised lands – the bigger the family, the more we get back”), the self-revealing phrases Emma and her female friends use to concoct possibly imaginary personal ads. Above all there’s the horrible scene in which assorted women audition for the role of extras in a historical epic with clear soft-porn overtones – though the montage of hopefuls could hardly be less sensually staged. Framed full-length and stark naked, they give their names and jobs before Szabó cuts to the next, creating a continuous litany that tells its own depressing story: teacher, nurse, teacher, teacher, waitress, nursery supervisor, nurse, teacher…

Everyone seems poised on the brink of something calamitous. Stefanics offers the most acute analysis of the malaise affecting his colleagues: they used to be secure in collective mediocrity, but now they’re individual nobodies, and all too disposable. The policeman who interviews Emma pauses for reflection: like Szabó himself, he’s in his fifties, and has seen his world turned upside down six times, to the point where his primary motive is simple survival. Emma herself has a moment of self-reflection when performing an errand for an elderly woman in church, in the closest anyone gets to offering up an actual prayer in an otherwise aggressively secular world, though she undercuts this by affirming her lack of faith. The only person who seems broadly content with his lot is the sketch artist Szilárd, the walls of whose room are covered with mementoes of his brief conquests, though even he is forced to time things to the hour, lest his roommate complain about him hogging the room for too long.

Szabó shot the film for a much lower budget than he was normally used to (reportedly under $500,000), and so consequently opts for quasi-Ken Loachian location-shot realism, aside from Emma’s slow-motion dreams. That said, he and regular cinematographer Lajos Koltai can’t resist the odd visual flourish: an outwardly banal shot of Emma having a break while cleaning a well-appointed bourgeois flat is framed and lit like a Vermeer, while the occasional brief reverie is sometimes underscored by Robert Schumann piano pieces, an incongruous segue into quiet, limpid beauty before the latest horror erupts in Emma and Böbe’s lives. And if Sweet Emma, Dear Böbe is a gruelling watch for much of the time, it has every excuse: neither Szabó nor anyone else in Hungary knew where things were heading. Indeed, in the wake of Hungary’s recent economic crisis, much of the film is just as bleakly relevant today.

- Director: István Szabó

- Screenplay: István Szabó

- Story: István Szabó, Andrea Vészits

- Photography: Lajos Koltai

- Set Design: Attila Kovács

- Costume Design: Zsuzsa Stenger

- Music: Mihály Móricz, Tibor Bornai, Feró Nagy, Robert Schumann

- Editing: Eszter Kovács

- Sound: György Kovács

- Producer: Gabriella Grósz

- Cast: Johanna ter Steege (Emma – dubbed by Ildikó Bánsági); Enikő Börcsök (Böbe); Péter Andorai (Stefanics); Éva Kerekes (Sleepy); Irma Patkós (Patient); Erzsi Pásztor (Teacher); Hédi Temessy (Mária); Irén Bódis (Emma’s Mother); Erzsi Gaál (Mrs. Horváth); Zoltán Mucsi (Szilárd); Tamás Jordán (Detective); Gábor Máté (Policeman)

- Production Company: Objektív Film

Links

- Internet Movie Database

- Variety database

- Reviews: The Guardian (Derek Malcolm); Time Out (Colette Maude)