Warszawa 1956

Warszawa 1956

Poland, 1956, black and white, 10 mins

Essentially a cross between Edgar Anstey and Arthur Elton’s classic British documentary Housing Problems (1935) and a particularly sadistic child-in-peril suspense thriller, Warsaw ’56 is the most sheerly terrifying film in the ‘black series’ of documentaries that shook up Polish cinema in the mid-1950s. Although it uses similar shock tactics to those of Jerzy Hoffman and Edward Skórzewski in their breakthrough films Look Out, Hooligans! (Uwaga chuligani!, 1955) and The Children Accuse (Dzieci oskarżają, 1956), the build-up is much subtler, starting with the deceptively tranquil title (no exclamation marks or finger-pointing words like “accuse”) and continuing through an initially sober and unsensationalised account of the problems of finding suitable housing in a city that’s still rebuilding after the devastation of only just over a decade earlier.

Certainly, Warsaw in 1956 looks impressive, an exemplar of modern urban planning that’s a delight to live and work in. As the regular WFD commentator Andrzej Łapicki implies at the start, it’s easy to put together a newsreel praising Warsaw to the skies – a few scene-setting aerial shots, people strolling around contentedly, narration tossing out statistics about the number of new squares, housing estates and playgrounds, a pan up the front of the Palace of Culture and Science at precisely the right angle so that its spire can catch the sun’s reflection as though it was some kind of beacon. “But 1956 is different”, says Łapicki, “the chronicler watches more carefully and sees what he earlier tried not to see.” – a neat way of acknowledging that Polish filmmakers had more freedom in 1956 than they’d had when Stalinist Socialist Realism was the universally-imposed norm.

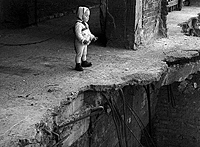

This change in tone is accompanied by an even more dramatic shift in visual content – we’re now looking behind the façades, at people who live in multi-storey apartments that are still visibly bombed-out, with vertiginous plunges awaiting anyone who missteps – we soon see an example of a boy with his leg in plaster who ran out of his room straight over the precipice (and, as Łapicki adds, somewhat callously, has only himself to blame). Clutching onto rickety railings, children look up at holes that run through several floors, still tracing the trajectory of bombs dropped a dozen years before – in one neatly macabre touch that foreshadows what’s to come, a small boy tosses a paper plane into one of these artificial shafts.

Surely no-one could live in buildings that would have present-day health and safety officials rushing to board them up? (These dwellings make the notorious slums of Housing Problems look like luxury flats by comparison.) But they do, living alongside beetles and cockroaches and tying their children to the bed or other items of furniture if they think their attention is likely to be distracted – for instance, doing the washing in an old-fashioned washboard, or changing a strip of fly-paper that’s become caked in black dots.

Just after the halfway mark, the film shifts into its second act, and the one that gives it its reputation as a miniature masterpiece of suspense to rival anything in Hitchcock and Clouzot’s catalogues. As the father of two young children myself, I have to admit that this sequence is perilously close to being unwatchable – and that’s not remotely a criticism of directors Jerzy Bossak and Jarosław Brzozowski, who clearly intended precisely this reaction. Up to this point, the soundtrack has been entirely non-diegetic, consisting entirely of deceptively jaunty accordion music and Łapicki’s narration. Now, direct sound takes over, a carefully-calibrated parade of creaks and groans that emphasise the building’s appalling fragility – accompanied by the hesitant footsteps of a toddler who has managed to break free, dragging the string that tied him to the bed behind him like a perverse variation on Ariadne’s thread. Bossak and Brzozowski use every suspense tactic at their disposal, and when the toddler spots a pigeon and starts to chase after it, many viewers will be watching through their fingers.

After this tour de force, there’s not much to add: the point has been made more than eloquently. However, Łapicki’s narration resumes in the closing minute with a surprisingly blunt attack on a system that allows umpteen new office spaces to be created while 6,000 Warsaw citizens are waiting for basic accommodation. This is an even more direct example of the anti-bureaucracy line taken by many films in the ‘black series’ (the same year’s Where the Devil Says Goodnight/Gdzie diabeł mówi dobranoc and Little Town/Miastecko, 1957’s Place of Residence/Miejsce zamieszkania). Were Warsaw ’56 to be double-billed with Wojciech Has and Stanisław Różewicz’s classic Brzozowa Street (Ulica Brzozowa, 1947), the film’s main argument would have even greater force – in nearly a decade, despite all sorts of cosmetic improvements in the higher-profile parts of the city, the neglected areas are just as badly off as before.

- Directors: Jerzy Bossak, Jarosław Brzozowski

- Editor: Waclaw Kaźmierczak

- Sound: Halina Paszkowska

- Narration: Andrzej Łapicki

- Sound Editor: Stefan Zawarski

- Production Company: Wytwórnia Filmów Dokumentalnych (Documentary Film Studio)

The film is included on PWA’s Polish School of the Documentary: The Black Series double-DVD set (Region 0 PAL). Although most of the print is up to the same standard as those elsewhere on the set, the start and end are somewhat battered – at the beginning, a particularly unfortunate splice has eliminated what I presume to be the cinematographer and music credits (hence their absence above). There’s also a fair bit of exposure fluctuation and a couple of tramlines. However, these rough edges don’t work against the film’s theme – quite the reverse. Aside from a couple of minor wording-related niggles, the subtitles are fine.