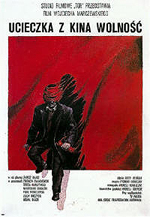

Ucieczka z kina ‘Wolność’

Ucieczka z kina ‘Wolność’

Poland, 1990, colour, 87 mins

Premiered on 15 October 1990, just over a year after the election of Poland’s first non-communist government in over four decades, Wojciech Marczewski’s Escape from the ‘Liberty’ Cinema offers a bizarre but rather engaging combination of anti-communist satire and film-versus-reality metaphysical trickery in the manner of Buster Keaton’s Sherlock, Jr. (1924) or Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985).

Set at some unspecified point in the late 1980s (between the release of Allen’s film and the fall of communism), the film revolves around the travails of the rumpled, careworn Rabkiewicz (Janusz Gajos), a provincial censor who clearly hates his job – it literally gives him a headache – but was presumably unable to find a sufficiently appealing alternative. He may well see himself as a frustrated artist, if his self-justifying speech explaining the creativity of censorship is any guide: those pesky artists won’t say “down with Communism!” outright, so he has to interpret their work. He’s also surrounded by knaves and fools, notably his candyfloss-addicted deputy (Zbigniew Zamachowski), whose self-caused difficulties Rabkiewicz is often called upon to resolve.

However, Rabkiewicz’s real problems begin with what looks like a banal romantic melodrama by the name of Daybreak (Jutrzenka), that’s playing in the ‘Liberty’ cinema opposite his office. Judging from the extracts that we see, there’s nothing apparently exceptionable about it (or anything exceptional: it looks like a very dull melodramatic weepie) until one of the actors, playing an elderly music professor, abandons the script to confess that “he couldn’t give a fuck” about his protégée’s chances in the Chopin competition. Though this goes down a storm with the hitherto bored school party that makes up much of the ‘Liberty’s audience, the manager realises that the film isn’t finishing on time, because the actors are mounting a full-scale mutiny against the banality of what they’re forced to perform in. (“I was brought up on Sophocles, where life and death have dimension and gravity”).

Unable to come up with a plausible explanation for this, but legally incapable of shutting down a film that’s been officially passed as suitable for screening (Marczewski has a lot of fun mocking bureaucratic red tape), Rabkiewicz concocts an elaborate plan that will involve keeping the cinema open but empty, subsidising the management for its losses. (This part seems to satirise the common Eastern bloc practice whereby troublesome films would get given a deliberately limited release, usually out in the sticks well away from the equally troublesome target audience). But this is expensive, so Rabkiewicz’s superiors pay him and the cinema a visit to assess the situation. They also bring along a film critic to judge the merit of what’s on screen – which by then has turned into an endless whingefest as the more activist actors are challenged by those who just want to finish the job and go home.

The critic pronounces his judgement: the problem with Daybreak is that it’s a Polish film, and therefore it’s cliché-ridden, ponderous and full of longueurs. Cinema should have sweep and imagination, whereas this is dull and provincial. To illustrate how the Americans do it properly, he runs a reel of The Purple Rose of Cairo – but an accident in the projection box causes both films to get mixed up, with its pith-helmeted lead ending up in ‘Daybreak’, which continues to unspool. (Unsurprisingly, Jeff Daniels did not reprise his role here, but his replacement does a surprisingly adequate job – helped by Marczewski shooting him from behind and from a distance to hide the deception).

Truth be told, this explicit citation of Purple Rose (and implied nod to Buster Keaton) sets the film a comedic standard that it ultimately can’t measure up to, very funny though it often is. But the anti-censorship elements are entirely Marczewski’s, and in this respect the film becomes a fascinating and oddly moving time capsule of an era in which Polish filmmakers were slowly emerging blinking into post-communist light.

There’s a particularly delightful running gag in which people burst into snatches of Mozart (not opera, as some commentators have claimed, but the Requiem – which seems more appropriately symbolic), seemingly just for the hell of it, anticipating the flash-mob phenomenon by nearly two decades. There’s also a more sombre scene, set on a rooftop, in which Rabkiewicz (who has found a way of entering ‘Daybreak’ in order to escape his colleagues) is confronted by actors whose careers were ruined by his often arbitrary decisions to censor their work – and it’s at moments like these that Marczewski can’t help but betray his anger at a system that stifled so much talent, often out of entirely misplaced paranoia.

There’s a sly nod to Dostoyevsky here in the presence of a shadowy figure credited as ‘Raskolnikov’ at the end – one of many literary references in the film, which seems to be striking a blow for intelligent, cultured cinema of a type that, ironically, would be more seriously threatened by naked capitalism than it ever was under communism. On its original release, Escape from the ‘Liberty’ Cinema must have seemed wonderfully optimistic and Utopian – almost a petition for Polish cinema to get its cultural act together (Robert Altman would send a similar message to Hollywood via The Player two years later). The fact that no-one listened and that post-1989 Polish cinema has generally been far less distinguished than its output from 1969-89 makes the film a more sobering experience today than must have been the case back in 1990.

Which may explain why Marczewski’s film rapidly faded into undeserved obscurity: if a truthful message has implications that are hard to take on board, Rabkiewicz and his ilk would doubtless advise that it should be suppressed, and neglect is just as effective a method as outright censorship (more effective, in fact, as people are much less likely to notice). And the subsequent fate of the film underscores the fact that censorship continued to function in Poland after 1989 – but in much subtler and more insidious ways.

- Director/Script: Wojciech Marczewski

- Photography: Jerzy Zieliński

- Production Design: Andrzej Kowalczyk

- Costume Design: Ewa Krauze

- Editor: Elżbieta Kurkowska

- Sound: Mariusz Kuczyński, Joanna Napieralska

- Music: Zygmunt Konieczny

- Production Manager: Andrzej Sołtysik

- Cast: Janusz Gajos (censor Rabkiewicz), Zbigniew Zamachowski (assistant censor), Teresa Marczewska (Małgorzata), Piotr Fronczewski (Party Secretary), Władysław Kowalski (Professor), Michał Bajor (Film Critic), Jan Peszek (Raskolnikow), Jerzy Bińczycki (cinema manager), Artur Barciś (Krzysio, the projectionist), Maciej Kozłowski (American actor), Henryk Bista (comrade Janik), Ewa Wencel (censor’s secretary), Krzysztof Wakuliński (Jerzy, assistant professor, Zofia Tomaszewska-Grąziewicz (‘Liberty’ cinema cashier), Aleksander Bednarz (Edward), Krystyna Tkacz (nurse), Zygmunt Bielawski (doctor, psychiatric hospital), Ewa Wiśniewska (censor’s ex-wife), Monika Bolly (Marta Rabkiewicz, censor’s daughter), Jerzy Gudejko (doctor), Eugenia Herman (teacher in charge of school party), Włodzimierz Musiał (militia officer), Eugeniusz Korczarowski, Tadeusz Falana, Stanisław Jaroszyński, Ryszard Mróz, Maria Wawszczyk, Szymon Herman, Jan Hencz (official delegation)