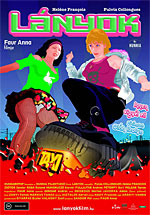

Lányok

Lányok

Hungary, 2007, colour, 90 mins

The opening titles of Anna Faur’s disturbing feature debut begin with what looks like a standard disclaimer about the events and people depicted in the film being imaginary – presumably a Hungarian audience would have picked up on the fact that she sourced her material from a true story that hit the headlines in 1997, when a taxi driver was murdered for no apparent reason by two teenage girls.

The murder in question forms the film’s final act, though the film has hardly been a thriller up to then – it’s much closer to a Hungarian equivalent of Larry Clark’s vividly-staged but almost unwatchably bleak Kids (US, 1995). The kids here (the average age seems to be fourteen) lead lives that are just as empty and pointless: a particularly hideous teenage party features two boys openly masturbating on the sofa to hard-core pornography while girls are groped and fingered in dark corners or bathrooms. Sex has become entirely commodified – there’s not even the faintest sense that it has any emotional function, and the adults are just as culpable as the teens, only without the excuse of ignorance.

The girls of the title are Dini (Fulvia Collongues) and Anita (Hélène François), who spend their time truanting, hanging around shopping centres and fairgrounds, and offering sexual favours to taxi drivers, either for money or in exchange for driving lessons. Dini is by some distance the film’s most horribly convincing character, ruthlessly exploiting every opportunity that comes her way (she makes it clear to her occasional lover Anita that she feels nothing for Zsolti (Tamás Polgár), the boy she’s hitting on – she seems more interested in the possibilities offered by a weekend in his rich parents’ house). Anita does at least have a mother, but there’s no sign of any authority in Dini’s life, and she seems to have no moral compass whatsoever – although she’s constantly accusing Anita of embarrassing her, she scarcely seems to understand the meaning of the word, with her casual alfresco public urination, feeding a stray dog by chewing and spitting out gobbets of sandwich, and casual handbag theft (followed by the wholesale destruction of its contents, including sentimental postcards, once it fails to yield the desired riches). That said, she does hint at a tiny degree of shame when she visibly bridles at being called a whore, the wealth of supporting evidence notwithstanding. Collongues’ fiercely charismatic performance – Dini is not, to put it mildly, the kind of person you want to get in an argument with – is the strongest in the film by some margin, completely belying her lack of experience.

The more fastidious Anita is largely in Dini’s shadow – she’s happy to go along with her friend’s exploits but draws the line at participation unless it’s unavoidable (and for instance, clubbing Dini’s client on the back of the head while he’s otherwise distracted). Unlike Dini, she does seem genuinely hurt by emotional slights, especially when Zsolti callously (and mendaciously? Who knows?) tells her that he and Dini don’t ever mention her when they’re together. She lives with her mother in a small flat full of tacky tourist souvenirs, which she finds both repellent and compelling – at least in providing her with the ambition to flee at all costs (the lyrics of the soundtrack songs are frequently about the joys of escape).

The film’s other main character is Ernő (Sándor Zsótér), one of the taxi drivers, who seeks regular sexual relief from Dini as an all too temporary escape from a completely loveless marriage – and a couple of scenes suggest that if it wasn’t for Dini’s ready availability, he’d be pressing his attentions onto his young daughter. His wife Rita openly despises him, blaming his constant (if fruitless) quests for a fast buck (which largely revolve around insurance fraud – his deliberately engineered crashes are an adult equivalent of Dini and Anita’s dodgem-car rides) as the reason she hasn’t been able to afford treatment for her acne-pitted face, though her chainsmoking can’t have helped. She says she’s only staying in the marriage for the sake of their daughter, but her despairing view of their future is summed up by her wish that she’d will end up fat so that boys won’t find her attractive. She’s close friends with Ildikó, who is married to Ernő’s colleague Béla, his usual partner in crime, and their children often play together, with cries of “stupid cocksucking faggot!” occasionally audible from their bedrooms. (“Touch them again and I’ll break your arm”, says Béla to his son Tibi when he catches him fighting with Ernő’s daughter).

Faur’s approach is generally ultra-realistic, with many characters shown in calculatedly unflattering close-up. Occasionally, though, she and cinematographer András Gondár strive for something more poeticised, such as a mid-point scene in which the camera tracks Anita as she walks past a long stretch of waste ground, or the scene where Dini and Anita achieve a tentative reconciliation while balancing precariously on large silver pipes. The film’s final act, in which an attempted robbery turns into a full-blown murder (though the identity of the victim isn’t what one might have expected from the foregoing), recalls the equivalent scenes in Alfred Hitchcock’s Torn Curtain (US, 1966) or, more pertinently given the victim’s occupation, Krzysztof Kieślowski’s A Short Film About Killing (Krótki film o zabijaniu, Poland, 1987), in that it’s agonisingly drawn-out, the girls’ expected scenario whereby he conveniently crumples at the first blow of a Coke bottle to the back of the head, proving as misguided and poorly thought-through as all their other plans.

But though Dini and Anita’s culpability is never in doubt, Faur never points an accusing finger directly at them – she clearly regards the ghastliness of their background and the nonexistent opportunities for advancement as being just as responsible for their actions. Regardless of their immediate financial or family situation, all the film’s characters are scraping an existence on the very margins of society. She acknowledges the influence of Luc and Jean-Pierre Dardenne (whose 2005 film L’Enfant also showed how the need for survival will always trump morality) and her compatriot Kornél Mundruczó (who plays a supporting role here), though the fact that she’s presenting not merely a female point of view but an alarmingly unvarnished one means that Girls has its own considerable value – even if it’s not a film most people will want to watch more than once.

- Director/Screenplay: Anna Faur

- Photography: András Gondár

- Editor: Vanda Arányi

- Music: Márton Hegedűs, Ádám Jávorka

- Producer: Pál Sándor

- Production Company: Hunnia Filmstúdió

- Cast: Fulvia Collongues (Dina), Hélène François (Anita), Sándor Zsótér (Ernő), Roland Rába (Béla), Kornél Mundruczó (Péter), Andrea Fullajtár (Rita), Bori Péterfy (Ildikó), Támas Polgár (Zsolti), Kata Rónai (Ernő’s daughter), Tibor Karajos (Béla’s son), Alexa Szabó (Béla’s daughter), Panni Faur (Injured woman), Bertalan Sugár (Passenger)