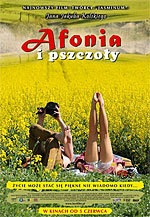

Happy Aphonia (Afonia i pszczoły, d. Jan Jakub Kolski, 2009).

Happy Aphonia (Afonia i pszczoły, d. Jan Jakub Kolski, 2009).

With films like Pornography (Pornografia, 2003) and Jasminum (2006), Jan Jakub Kolski established himself as one of modern Polish cinema’s more striking individualists, attracting comparisons with Federico Fellini and Emir Kusturica. These are still valid for Happy Aphonia (also known as Aphonia and Bees, a literal translation of the Polish title), but this time as a reminder that Fellini and Kusturica were also prone to wilful self-indulgence at the expense of much discernible point. It’s set after Stalin’s death in 1953 (protagonist Aphonia still wakes to a Stalin-faced alarm clock) but before the Khrushchev thaw of 1956, when Poland was still recovering from World War II and deeply uncertain about the intentions of its Soviet neighbour. The primary location is a converted railway station that Aphonia (the director’s wife Grażyna Błęcka-Kolska) shares with her paraplegic husband Ralph (Mariusz Saniternik), a former wrestler turned Leonardo-like visionary following a rooftop fall. This seems to work well, until their seclusion is invaded by an unnamed Russian soldier (also a former wrestler, natch, and there are more to come) who sweeps Aphonia off her feet and into a state of histrionic but unconvincing amour fou that culminates in attempted suicide and a climactic scene of self-mutilation that’s both viscerally unpleasant and wildly implausible. But this is long after the film has been reduced to a succession of contrived magical-realist set-pieces and much self-conscious symbolism (particularly involving a trapped bee that Aphonia gives the Russian), intermittently striking but collectively incoherent.

Mall Girls (Galerianki, d. Katerzyna Rosłaniec, 2009)

Mall Girls (Galerianki, d. Katerzyna Rosłaniec, 2009)

Expanded from a film-school short that Katarzyna Rosłaniec made in 2006 (which can be watched on YouTube, albeit only in unsubtitled Polish), this was one of the competition’s most pleasant surprises, and the jury’s unanimous and near-instant choice for Best Debut. Low expectations were engendered by overly familiar material – the agonies of adolescence, the travails of school, the pressing social need to maintain a carefully-nurtured image through clothing, make-up and branded accessories – but Rosłaniec turns out to have a genuinely fresh eye (aided by the veteran Witold Stok’s colourful Scope cinematography) and a real gift for extracting heartfelt performances out of an inexperienced teenage cast. The most outstanding is Anna Kaczmarczyk as Ala, convincingly negotiating the journey from shy swot to sultry sexpot while never losing sight of her character’s emotional fragility. An eleventh-hour lurch into melodrama when a central character commits suicide is a tad contrived, but Rosłaniec generally takes considerable and commendable pains to avoid the obvious: stereotyping and finger-wagging moralising are kept to a minimum, even when dealing with subjects like drugs, fumbling adolescent sexuality, teenage pregnancy and even casual prostitution. Minor characters are deftly sketched in seconds: we don’t see much of Ala’s family, but enough to make it clear that its outward normality hides a core as dysfunctional as that of the far more obviously broken homes that spawned her friends. Marx once preached the abolition of the family as one of communism’s goals, but Rosłaniec makes it clear that consumer capitalism is more than capable of wreaking just as much destruction.

The Miracle Seller (Handlarz cudów, d. Bolesław Pawica/Jarosław Szoda, 2009)

The Miracle Seller (Handlarz cudów, d. Bolesław Pawica/Jarosław Szoda, 2009)

This joint feature debut from former music video directors Bolesław Pawica and cinematographer Jarosław Szoda is essentially a fairly standard-issue road movie (Stefan, a former alcoholic turned born-again Lourdes pilgrim, finds to his initial discomfiture that he’s being unwittingly accompanied by two child refugees from Dagestan in search of their France-based father) but it’s boosted by good performances and strong individual sequences, notably a nocturnal border crossing via a river with the aid of empty plastic fuel cans to aid buoyancy. The film also does a rather better job than rival competition entry My Flesh, My Blood in highlighting the problems of being part of a persecuted minority in contemporary Poland: the gut-instinct prejudice or worse that Urika (Sonia Mietielica) and Hasim (Roman Gonczuk) routinely encounter from everyone from shopkeepers to taxi drivers almost justifies their usually antisocial (sometimes actively criminal) response, and they contemptuously refer to Stefan as ‘the Pole’ despite becoming increasingly dependent on his goodwill. But when they reach their destination it becomes cruelly apparent that far from living an instinctively lawless existence, they’re actually bound by ancient codes that dictate the arc of their lives almost from birth. Polish cinema’s man of the moment Borys Szyc is unrecognisable from his snarling turn in in Xawery Żuławski’s Snow White and Russian Red/Wojna polsko-ruska – here, his Stefan is a world-weary sad-sack, his receding hairline capped with a prominent widow’s peak, while the two children prove to be naturals.