Tatarak

Tatarak

Poland, 2009, colour, 85 mins

- Director: Andrzej Wajda

- Screenplay: Andrzej Wajda (and, uncredited, Krystyna Janda), based on the story by Jarosław Iwaskiewicz

- Photography: Paweł Edelman

- Production Design: Magdalena Dipont

- Costume Design: Magdalena Biedrzycka

- Music: Paweł Mykietyn

- Sound: Jacek Hamela

- Editing: Milenia Fiedler

- Producer: Michał Kwieciński

- Cast: Krystyna Janda (Marta, herself), Paweł Szajda (Boguś), Jan Englert (doctor, Marta’s husband), Jadwiga Jankowska-Cieślak (Marta’s friend), Julia Pietrucha (Halinka), Roma Gąsiorowska (maid), Krzysztof Skonieczny (Stasiek), Paweł Tomaszewski, Mateusz Kościukiewicz, Marcin Łuczak (bridge players), Andrzej Wajda (himself), Michał Kasprzak, Krystian Kopański, Marcin Korcz, Karol Kosik, Maciej Kowalik, Arkadiusz Lewicki, Tomasz Łukaszewski, Magdalena Michel, Jarosław Panter, Agnieszka Sowa, Maciej Świtajski, Zbigniew Sznitko

- Production Company: Akson Studio

Unlike the long-gestating, big-budget Katyń (2007), Andrzej Wajda’s new film was shot relatively quickly with a small cast and on a comparatively low budget, and premiered less than eighteen months after its predecessor at this year’s Berlin Film Festival, where it shared the Alfred Bauer prize. But despite several significant differences in scale and ambition, Katyń and Sweet Rush share one crucial element: both films were inspired by the real-life death of a loved one, respectively Wajda’s father Jakub (a presumed Katyń victim), and the cinematographer Edward Kłosiński, who lost his battle with lung cancer on 5 January 2008. Not only had Kłosiński worked with Wajda on several films, but he was also lead actress Krystyna Janda’s husband.

Unlike the long-gestating, big-budget Katyń (2007), Andrzej Wajda’s new film was shot relatively quickly with a small cast and on a comparatively low budget, and premiered less than eighteen months after its predecessor at this year’s Berlin Film Festival, where it shared the Alfred Bauer prize. But despite several significant differences in scale and ambition, Katyń and Sweet Rush share one crucial element: both films were inspired by the real-life death of a loved one, respectively Wajda’s father Jakub (a presumed Katyń victim), and the cinematographer Edward Kłosiński, who lost his battle with lung cancer on 5 January 2008. Not only had Kłosiński worked with Wajda on several films, but he was also lead actress Krystyna Janda’s husband.

Janda had already been cast in her first Wajda film in nearly three decades (she’d previously headlined Man of Marble/Człowiek z marmuru in 1976, The Conductor/Dyrygent in 1980 and Man of Iron/Człowiek z żelaza in 1981), and by all accounts it was originally planned as a straightforward adaptation of a short story by Jarosław Iwaskiewicz, one of Wajda’s favourite writers – other Wajda-Iwaskiewicz adaptations include The Birch Wood (Brzezina, 1970) and The Young Ladies of Wilko (Panny z Wilka, 1979), on both of which Kłosiński also worked. Set shortly after World War II, it’s a drama about a middle-aged woman who is diagnosed with, but not informed about, a terminal lung condition, and who embarks on a fleeting romance with a young man in his early twenties. Apparently Wajda was a little concerned that this might be too thin for a full-length feature, but the project went into pre-production with Janda in the lead – and then delayed because Kłosiński’s condition worsened and Janda made it clear that he was her main priority. Unwilling to cast anyone else (understandably, in view of the finished film), Wajda was happy to wait – but Kłosiński’s death led to a radical rethink of the overall shape.

Janda had already been cast in her first Wajda film in nearly three decades (she’d previously headlined Man of Marble/Człowiek z marmuru in 1976, The Conductor/Dyrygent in 1980 and Man of Iron/Człowiek z żelaza in 1981), and by all accounts it was originally planned as a straightforward adaptation of a short story by Jarosław Iwaskiewicz, one of Wajda’s favourite writers – other Wajda-Iwaskiewicz adaptations include The Birch Wood (Brzezina, 1970) and The Young Ladies of Wilko (Panny z Wilka, 1979), on both of which Kłosiński also worked. Set shortly after World War II, it’s a drama about a middle-aged woman who is diagnosed with, but not informed about, a terminal lung condition, and who embarks on a fleeting romance with a young man in his early twenties. Apparently Wajda was a little concerned that this might be too thin for a full-length feature, but the project went into pre-production with Janda in the lead – and then delayed because Kłosiński’s condition worsened and Janda made it clear that he was her main priority. Unwilling to cast anyone else (understandably, in view of the finished film), Wajda was happy to wait – but Kłosiński’s death led to a radical rethink of the overall shape.

Now, instead of being a linear period drama, it interweaves three separate elements. One is the original Iwaskiewicz material, the second depicts Wajda and Janda themselves working on the film (and consequently having to deal with material that opens up raw real-life wounds to do with terminal illness and sudden death), while the third is a lengthy three-part monologue delivered by Janda in an anonymous hotel room about Kłosiński’s diagnosis, decline and death. Wajda said that he and cinematographer Paweł Edelman were inspired by the American painter Edward Hopper when lighting these sequences, and it’s also worth noting that Janda delivers most of her monologue either facing away from the camera or with her head in shadow. Only the undoubted fact that Janda asked for the camera to be present (and the words are hers too) prevents the overall effect from being uncomfortably voyeuristic, though we’re not so much eavesdropping on deeply private grief as sharing a genuine emotional catharsis.

Now, instead of being a linear period drama, it interweaves three separate elements. One is the original Iwaskiewicz material, the second depicts Wajda and Janda themselves working on the film (and consequently having to deal with material that opens up raw real-life wounds to do with terminal illness and sudden death), while the third is a lengthy three-part monologue delivered by Janda in an anonymous hotel room about Kłosiński’s diagnosis, decline and death. Wajda said that he and cinematographer Paweł Edelman were inspired by the American painter Edward Hopper when lighting these sequences, and it’s also worth noting that Janda delivers most of her monologue either facing away from the camera or with her head in shadow. Only the undoubted fact that Janda asked for the camera to be present (and the words are hers too) prevents the overall effect from being uncomfortably voyeuristic, though we’re not so much eavesdropping on deeply private grief as sharing a genuine emotional catharsis.

These moments are so powerful that they threaten to unbalance the rest of the film, which I suspect is why Wajda and Janda introduced a third narrative strand, in which they’re shown working on the film adaptation in the wake of Kłosiński’s death, with Janda clearly overcome by the experience – so much so that she runs off the set during a particularly traumatic scene, to be picked up by a surprised motorist in the rain. For me, this was the least successful part of the film: although Wajda is at considerable pains to minimise any potential lurch into melodrama, it felt like an unnecessary pendant to what is already a strongly autobiographical piece.

These moments are so powerful that they threaten to unbalance the rest of the film, which I suspect is why Wajda and Janda introduced a third narrative strand, in which they’re shown working on the film adaptation in the wake of Kłosiński’s death, with Janda clearly overcome by the experience – so much so that she runs off the set during a particularly traumatic scene, to be picked up by a surprised motorist in the rain. For me, this was the least successful part of the film: although Wajda is at considerable pains to minimise any potential lurch into melodrama, it felt like an unnecessary pendant to what is already a strongly autobiographical piece.

But the Iwaskiewicz-sourced material works very well indeed, the early diagnosis of the protagonist Marta’s terminal illness emphasised by a memorably surreal shot of her upper body, her chest framed by a 1940s X-ray machine, her face and clearly visible (and breathing) lungs in the same image. Her not-quite-romance with the twentysomething student Boguś also rings true, the effect enhanced by actor Paweł Szajda’s passing resemblance to Jerzy Radziwiłowicz, Janda’s co-star in Man of Marble and Man of Iron, although with a far bigger age gap between him and Janda. Like Wajda’s other Iwaskiewicz films, the overall effect is tranquil and contemplative, only occasionally broken by moments of high drama, though here it’s effectively contrasted with Janda’s monologue.

But the Iwaskiewicz-sourced material works very well indeed, the early diagnosis of the protagonist Marta’s terminal illness emphasised by a memorably surreal shot of her upper body, her chest framed by a 1940s X-ray machine, her face and clearly visible (and breathing) lungs in the same image. Her not-quite-romance with the twentysomething student Boguś also rings true, the effect enhanced by actor Paweł Szajda’s passing resemblance to Jerzy Radziwiłowicz, Janda’s co-star in Man of Marble and Man of Iron, although with a far bigger age gap between him and Janda. Like Wajda’s other Iwaskiewicz films, the overall effect is tranquil and contemplative, only occasionally broken by moments of high drama, though here it’s effectively contrasted with Janda’s monologue.

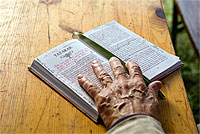

The title ‘Sweet Rush’ is a literal translation of the original ‘Tatarak’, though it’s potentially confusing to those who read the second word as a verb. Actually, Iwaskiewicz is referring to a type of lakeside reed, his description delivered verbatim on screen: “When crushed between your fingers its green ribbon, creased in places, will emit a scent, a mild fragrance of ‘water shaded by trees’, with a subtle touch of oriental balms. But when you sniff deep into a furrow, padded with something which resembles cotton wool, apart from the incense-like fragrance you can smell muddy loam, rotting fish scales or just mud. The smell of death.” Edelman enhances the impression by strongly favouring the colour green throughout – not the pallid, desaturated greens he used in Katyń but something much more vibrant and visibly alive. (One review of the Berlin premiere suggested that the on-set footage was in black and white, but this wasn’t true of the print that I saw in Wrocław).

The title ‘Sweet Rush’ is a literal translation of the original ‘Tatarak’, though it’s potentially confusing to those who read the second word as a verb. Actually, Iwaskiewicz is referring to a type of lakeside reed, his description delivered verbatim on screen: “When crushed between your fingers its green ribbon, creased in places, will emit a scent, a mild fragrance of ‘water shaded by trees’, with a subtle touch of oriental balms. But when you sniff deep into a furrow, padded with something which resembles cotton wool, apart from the incense-like fragrance you can smell muddy loam, rotting fish scales or just mud. The smell of death.” Edelman enhances the impression by strongly favouring the colour green throughout – not the pallid, desaturated greens he used in Katyń but something much more vibrant and visibly alive. (One review of the Berlin premiere suggested that the on-set footage was in black and white, but this wasn’t true of the print that I saw in Wrocław).

In its quiet, low-key contrast to its immediate predecessors, Sweet Rush occupies a position in Wajda’s output very similar to some of Akira Kurosawa and Ingmar Bergman’s late works: these are films by people who have nothing more to prove, and their tranquil, almost understated modesty is somehow immensely winning. I suspect it isn’t for everyone, and I know that it’s had some negative press – how much you respond to it seems to me to depend on how much you admire Janda in general, and how familiar you are with her and Wajda’s previous work (prior knowledge of the timing of Kłosiński’s death helps too, though you can probably glean what you need from the monologue), as well as your tolerance for the less successful elements. But for me it was Wajda’s most satisfying film since Korczak nearly twenty years ago.

In its quiet, low-key contrast to its immediate predecessors, Sweet Rush occupies a position in Wajda’s output very similar to some of Akira Kurosawa and Ingmar Bergman’s late works: these are films by people who have nothing more to prove, and their tranquil, almost understated modesty is somehow immensely winning. I suspect it isn’t for everyone, and I know that it’s had some negative press – how much you respond to it seems to me to depend on how much you admire Janda in general, and how familiar you are with her and Wajda’s previous work (prior knowledge of the timing of Kłosiński’s death helps too, though you can probably glean what you need from the monologue), as well as your tolerance for the less successful elements. But for me it was Wajda’s most satisfying film since Korczak nearly twenty years ago.

Links

- Official website, in English and Polish.

- Official Wajda website – at the time of writing, the page was uploaded prior to production, and gives an idea of Wajda’s original intentions for the film.

- Filmpolski.pl (in Polish)

- Internet Movie Database

- Reviews: The Hollywood Reporter (Kirk Honeycutt); Screen International (Dan Fainaru); Variety (Jay Weissberg)